Title page of Theodore Thomas’ score for Strauss’ Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks

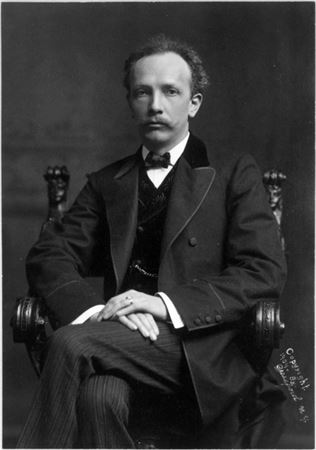

“While in Europe [during the summer of 1883] Theodore Thomas had, as usual, been on the lookout for musical novelties for coming programs. He had met, in Munich, a young and almost unknown composer, one Richard Strauss, who had recently finished writing a symphony,” wrote Rose Fay Thomas in her husband’s Memoirs. “Thomas secured the first movement of the work, and was so much impressed with it that he requested the young Strauss to let him have the other three movements, promising to bring out the whole work in a concert with the [New York] Philharmonic.”

However, in a letter to Thomas from Strauss dated a few months later on September 20, 1883, it appears that Thomas only met with Franz Strauss, Richard’s father and a noted horn player, composer and teacher. Nineteen-year-old Richard wrote: “As I was unfortunately unable to welcome you here this summer . . . I must not neglect to express to you in writing my heartiest and warmest thanks for your kind intention to give my second symphony the great honor of a New York performance.” Thomas kept his word and led the world premiere of Strauss’ Symphony no. 2 in F minor on December 12 and 13, 1884, thus introducing Strauss to America.

Their friendship blossomed, and as a result, Thomas later introduced several of Strauss’ tone poems to Chicago audiences, including the U.S. premiere of Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks during the Chicago Orchestra’s fifth season on November 15, 1895.

“In this work of the gifted young composer, we have a curious extravaganza, in which the entire resources of the modern orchestra are employed as a sort of summary of all conceivable pranks and freaks of elfins, fairies and gnomes, together with a thread of intelligible melody,” wrote W. S. B. Mathews in the program book. “At times the cacophony reaches a point where it seems as if we were listening to the preliminary overture of tuning and passage work, which everybody knows who has heard an orchestra tune up and warm up its instruments.”

The critical response was unanimous:

- “The Strauss rondo is probably the most fantastic piece of musical horse play that ever found place on a Chicago Orchestra program. It is eccentricity run mad, bedlam expressed in musical numbers.” — Chicago Times-Herald

- “It is, we can well believe, a marvelous piece of orchestration. More curious and inharmonious noises are woven together in it and the semblance of coherency maintained despite all the absurdities that we ever heard before in a sane composition.” — Chicago Chronicle

- “His absolute mastery of the resources of the modern orchestra may now find odd method of expression, but with years and their calming influence and with a firmer command of an imagination now fantastic to the verge of riot, to limit prediction of his possibilities would be something more than rash. Berlioz did not have his orchestra more completely in hand than Richard Strauss.” — Chicago Tribune

- “Strauss’ rondo is a tour de force, astonishing at every measure, irresistibly droll, full of quaint medieval quips and cranks, teeming with clever mimicry and brilliant instrumental pantomime, and, above all, a masterpiece of orchestral art. The intricacy of the score is extraordinary, the ingenious devices resorted to for effect amazing, and the humor and wholesome buffoonery of the piece unique. Nothing could have been chosen better to illustrate the immense resources of the young composer and the fertility of his genius. What is more, the piece gave the Orchestra an opportunity to display its consummate training, and it may be said that music never was played in Chicago with finer technical nicety or with more of the spirit of a composer.” — Chicago Record

Thomas repeated Till Eulenspiegel twice during that same season in early 1896 — on January 24 and 25 for a “Request Program” and again on February 28 and 29 for a “Requested repetition of the Request Program” — and programmed it five more times over the next eight years. The composer himself led his tone poem when he first guest conducted the Orchestra in April 1904.

Chicago Orchestra roster for the 1895–96 season

According to Phillip Huscher, the CSO’s program annotator and scholar-in-residence, Strauss begins his tale of the German peasant folk hero “by beckoning us to gather round, setting a warm ’once-upon-a-time’ mood into which the horn jumps with one of the most famous themes in all music — the daring, teasing, cartwheeling tune that characterizes this roguish hero better than any well-chosen words ever could.”

Principal horn during the 1895–96 season, Ernst Ketz (ca. 1853–ca. 1901) was likely sitting in the first chair for the U.S. premiere of Till Eulenspiegel on November 15, 1895, to play that theme, just ten days after the world premiere in Cologne, given by the Gürzenich Orchestra under the baton of Franz Wüllner.

A charter member of the Berlin Philharmonic in 1882, Ketz also performed regularly at the Bayreuth Festival from 1886 until 1894 and with the Gürzenich Orchestra in Cologne. In April 1893, he first traveled to the U.S. as a member of the Garde du Corps Cavalry Band, one of two military bands representing Germany at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. During the fair, Ketz’s name also appeared on the roster of the Exposition Orchestra, which was the Chicago Orchestra expanded to 114 players, led by Theodore Thomas.

Two years later, Ketz returned to the U.S. — at Thomas’ invitation — to be a member of the Chicago Orchestra, serving as principal horn. He stayed for only one season, after which he returned to Cologne. Ketz was back in the Gürzenich Orchestra for the world premiere of Strauss’ Don Quixote on March 8, 1898, again with Wüllner on the podium. Thomas led the U.S. premiere in Chicago on January 6, 1899.

This article also appears here, and portions previously appeared here.