Gustav Mahler in 1907

Moritz Nähr

In the 1960s and ’70s, when the Chicago Symphony Orchestra emerged as one of the world’s great Mahler orchestras, the wisdom of Mahler’s famous prediction, “My time will come,” was indisputable. During Mahler’s lifetime (1860–1911), the Orchestra played just one of his symphonies — the Fifth, which second music director Frederick Stock led on March 22 and 23, 1907, during the 16th season and little more than three years after the symphony’s premiere in Cologne, Germany. It was only the second of the Mahler symphonies to be played in the United States. Gradually, Stock continued to introduce Chicago to these unknown masterworks, adding the First Symphony in 1914, the Fourth in 1916 and one year later, the colossal Eighth, which he had wanted to program ever since he heard Mahler conduct the world premiere in Munich in 1910.

After Stock heard Mahler’s Seventh Symphony in Amsterdam in May 1920, at the inaugural Mahler Festival organized by the composer’s great advocate, Willem Mengelberg, Stock secured the U.S. premiere of the work for April 15, 1921, in Chicago — the only Mahler symphony that the Chicago orchestra introduced to this country. Still, despite Stock’s championship, no more Mahler symphonies were added to the Orchestra’s repertoire over the next three decades.

With the appointment of Rafael Kubelík as music director in 1950, Mahler’s music began to take hold in Chicago. In just three seasons, Kubelík led three of the symphonies and originally planned to close his second season with the Eighth. Although Kubelík had hoped to record the First Symphony, it was his successor, Fritz Reiner, who made the Orchestra’s first in a historic long line of Mahler recordings in 1958 with the Fourth Symphony, marking his own conversion to the composer’s music just as the Mahler craze was beginning to sweep the country. But the Orchestra had still never played the Third or Sixth symphonies — a half century after the composer’s death.

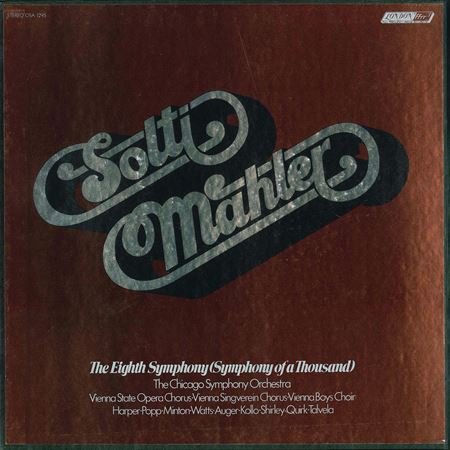

Only with the arrival of Georg Solti in 1969 did all of Mahler’s symphonies at last become part of the Orchestra’s regularly performed repertoire. Solti revived Symphony no. 5, which the Orchestra had only played once since its Chicago premiere in 1907; he programmed Symphony no. 7 for the first time in 37 years; and he led the Orchestra’s first performances of the Eighth since Stock introduced it 54 years earlier. It would take Solti more than a decade to work his way through the nine symphonies, and he would be the only music director in Chicago to perform and record the complete cycle, a set that was highly acclaimed and lavished with prizes.

In the years after Solti was succeeded as music director, first by Daniel Barenboim, and then by Riccardo Muti, their performances of Mahler’s music were now viewed as part of the Orchestra’s regular catalog rather than the exception, and the challenges to convert the public to the brilliance and power of these nine symphonies — and to demonstrate the Chicago orchestra’s particular affinity with them — were long past.

This spring, the Orchestra takes Mahler’s Sixth and Seventh symphonies, under Jaap van Zweden, to the third Mahler Festival in Amsterdam — revisiting the place Stock first heard the Seventh Symphony — as part of its European tour, and Zell Music Director Designate Klaus Mäkelä leads the Orchestra and Chorus in Mahler’s Third Symphony in Orchestra Hall. Mahler’s time is now.