Detail from solo cello part of Strauss' Don Quixote, used by Bruno Steindel (principal cello, 1891–1918) for the U.S. premiere in January 1899

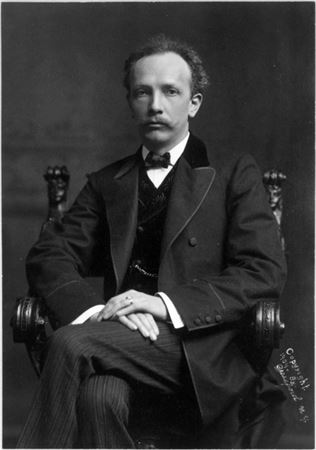

Theodore Thomas, the Orchestra’s founder and first music director, introduced the music of Richard Strauss in this country. According to his Memoirs (edited by his widow, Rose Fay Thomas), “While in Europe [during the summer of 1882] Thomas had, as usual, been on the lookout for musical novelties for coming programs. He had met, in Munich, a young and almost unknown composer, one Richard Strauss, who had recently finished writing a symphony. Thomas secured the first movement of the work, and was so much impressed with it that he requested the young Strauss to let him have the other three movements, promising to bring out the whole work in a concert with the [New York] Philharmonic.” Thomas kept his word and gave the premiere of Strauss’ Symphony no. 2 in F minor in New York on December 13, 1884.

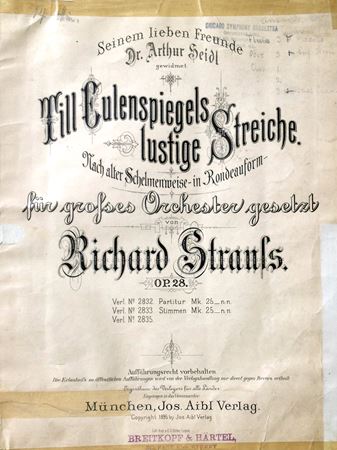

Thomas’s friendship with Strauss blossomed, and he later introduced several of the composer’s tone poems in the United States. With his eponymous ensemble — the Theodore Thomas Orchestra — he led Aus Italien in Philadelphia in March 1888. After founding the Chicago Orchestra in 1891, Thomas conducted the U.S. premieres of Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks in November 1895, Also sprach Zarathustra in February 1897, Don Quixote in January 1899 and Ein Heldenleben in March 1900.

For the first concerts of the new year in 1899, the first work heard after intermission was Strauss’ “Fantastic Variations on a Theme of Knightly Character.” “At first thought it would seem that any attempt to narrate musically the droll incidents of the masterpiece of Spanish fiction could result only in commonplaceness and failure,” wrote Hubbard William Harris in the program book. “But Strauss has scored a genius-stroke at the outset by the choice of the ‘variation’ form and by assigning personal themes to Don Quixote and Sancho Panza.”

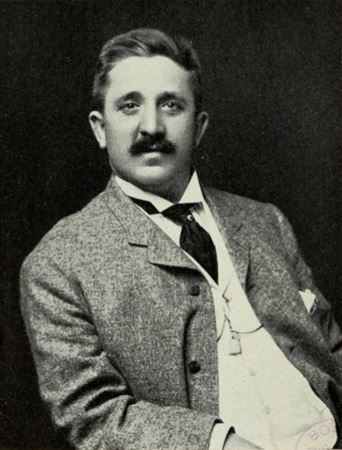

Following the first performance on January 6, the reviewer in the Chicago Tribune agreed. The work “exhibits the composer so strongly as a master of orchestral construction, the contrapuntal skill brought into play throughout the ten variations is so extraordinary. . . . The ’cello obligato which indicates Don Quixote was finely played by Mr. [Bruno] Steindel,* who entered into the humorous yet pathetic feeling of the character, and the prominence gave to the viola [played by Franz Esser**] in denoting Sancho Panza was a welcome recognition of a much neglected instrument.”

Strauss’ tone poem has remained a staple of the Orchestra’s repertoire, often featuring not only guest cellists — Pierre Fournier, Lynn Harrell, Antonio Janigro, Yo-Yo Ma and Gregor Piatigorsky — but also CSO principals — Edmund Kurtz, Robert LaMarchina, Frank Miller, Daniel Saidenberg, John Sharp, János Starker and Alfred Wallenstein — in the iconic role of Cervantes’s chivalrous knight-errant.

*Former principal cello of the Berlin Philharmonic, Bruno Steindel (1866–1949) had played under Brahms, Dvořák, Grieg, Richard Strauss and Tchaikovsky when he was chosen by Theodore Thomas as the Chicago Orchestra’s founding principal cello in 1891. One of a handful of musicians in the Orchestra who continued to express pro-German sentiments following U.S. involvement in World War I, Steindel and three other players were expelled from the Chicago Federation of Musicians in October 1918. He tendered his resignation effective at the beginning of the 1918–19 season. Steindel continued to perform in Chicago, as principal cello of the Chicago Civic Opera and giving concerts for the benefit of German war orphans, despite protests by American Legion posts. Steindel’s wife Mathilde, a pianist who frequently performed with the Steindel Trio (along with CSO violin Fritz Itte), had become depressed over the countless accusations her husband had received in the press. On the evening of March 5, 1921, she committed suicide by drowning herself in Lake Michigan. The next morning at the foot of Farwell Avenue, the police found her automobile (according to the Chicago Tribune), its lights “still ablaze. Her expensive fur coat, which she had cast off before jumping into the lake, lay on the pier.”

**Franz Esser (ca. 1868–1950) joined the violin section at the beginning of the second season in 1892, later serving as principal viola from 1898 until 1926 and principal second violin from 1926 until 1939. After more than 50 years of service, he retired in 1945.

This article also appears here.