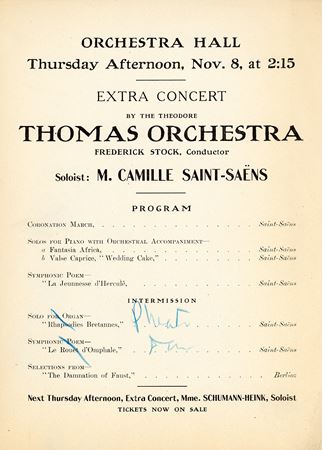

Advance notice in the program book for Saint-Saëns’ debut performances with the Orchestra in November 1906

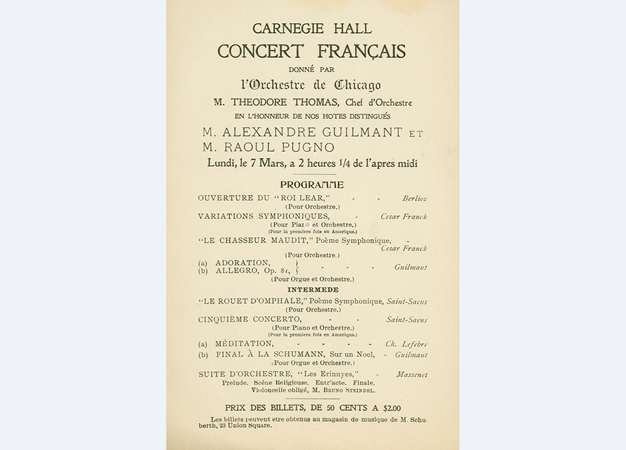

In March 1898, founder and first music director Theodore Thomas and the Chicago Orchestra embarked on a monthlong tour through Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Washington, D.C. In New York City, the tour included six concerts at the Metropolitan Opera House, one at the Brooklyn Academy of Music and the Orchestra’s debut in Carnegie Hall on March 7.

The program for Carnegie consisted entirely of music by French composers, featuring the U.S. premieres of César Franck’s Variations symphoniques and Camille Saint-Saëns’ Fifth Piano Concerto, both with Raoul Pugno as soloist. Composer Alexandre Guilmant also appeared, as organ soloist in his Adoration, Allegro and Final à la Schumann, as well as Lefebvre’s Méditation. Berlioz’s Overture to King Lear, Franck’s Le chasseur maudit, and Saint-Saëns’s Le rouet d’Omphale and Massenet’s Suite from Les Erinnyes rounded out the program.

The reviewer in Harper’s Bazaar praised the performances of both Pugno and Guilmant, “and the enjoyment of the afternoon was increased by the good work done by the Chicago Orchestra.” The New York Times added, “The Orchestra was heard to great advantage in Saint-Saëns’s symphonic poem, which was played with consummate finish, and Mr. Thomas’s accompaniments to the soloists were a source of joy.” And the New York Tribune heralded the concert as “an exhibition of virtuosity.”

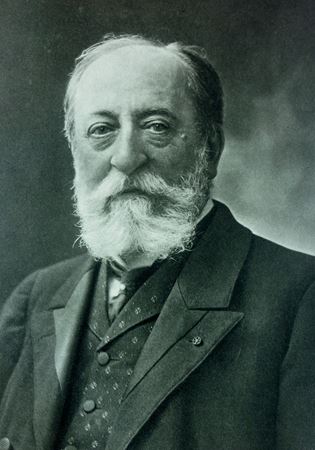

Eight years later, Saint-Saëns visited the United States for the first time in the fall of 1906, and his tour included a weekend of performances with the Orchestra. Demand for tickets was so great for the two scheduled subscription concerts featuring the composer that the Orchestral Association added an extra concert for November 8. That first appearance was “regarded as . . . one of the most important events of the season,” according to Glenn Dillard Gunn in the Chicago Inter Ocean. “Black haired, gray bearded, and immaculately dressed, he carries jauntily his seventy-two years of labor and honorable achievement in the realm of art. . . . His technical command of the piano is supreme. He has a velocity that is enormous, a certainty almost infallible.”

The first half of that extra concert included Saint-Saëns’ Coronation March, The Youth of Hercules and the composer at the piano for Africa and Wedding Cake, all conducted by Frederick Stock. Following intermission, it was announced that Saint-Saëns — who was still somewhat weak following a recent illness — would not perform the Bretonne Rhapsodies on the organ; instead, Stock would lead the Orchestra in Phaéton and the Danse macabre. Le rouet d’Omphale and selections from Berlioz’s The Damnation of Faust completed the program.

“When M. Saint-Saëns made his appearance he was given not only hearty greeting by the audience but by the Orchestra, and its leader as well. A ‘tusch’ from all the players welcomed him," reported the Chicago Tribune on November 9. "He plays with all the authority that is to be expected from a man who has been an acknowledged master for nearly a half century, and he plays with a technical accuracy, a clarity, and a beauty which would put many of our younger pianists to the blush. There is never the least forcing of the piano, and yet there never is lack of color in his work. His fortes and fortissimos are big and virile, but they are invariably musical and tonally fine. He has fingers that are exceptionally fleet, and the grace, elegance, and nice proportion that are characteristic of the French school of music are ever present in fascinating degree in his performance. . . . Mr. Stock and his men were on their mettle and gave accompaniments which were ideal.”

On the November 9 and 10 subscription concerts, Stock and the Orchestra repeated the Coronation March, Danse macabre and Phaéton. To close the first half of the program, Saint-Saëns was soloist in his Second Piano Concerto, and Dvořák’s New World Symphony was given following intermission. William Lines Hubbard in the Chicago Tribune noted the composer’s weak appearance. “When seated at the piano, however, the musician took predominance over the man, and positiveness, strength, and authority were in evidence. . . . We have several notable presentations of the graceful [G minor concerto], but none of them has been technically more beautiful, tonally more gratifying, or interpretatively more elegant than was the one he offered yesterday. . . . The Orchestra gave an accompaniment which could but have rejoiced the composer’s heart, and the audience grew insistently enthusiastic and would not be stilled until the veteran pianist returned to the instrument and gave an additional solo.”

This article also appears here.