The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s commercial recording legacy began on May 1, 1916, when second music director Frederick Stock led the Wedding March from Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream for the Columbia Graphophone Company. The Orchestra has since amassed an extraordinary, award-winning discography on a number of labels — including Angel, CBS, Deutsche Grammophon, Erato, London/Decca, RCA, Sony, Teldec, Victor and others — continuing with releases on the in-house label CSO Resound under tenth music director Riccardo Muti. For My Favorite CSO, we asked members of the Chicago Symphony family for their favorite recordings (and a few honorable mentions) from the Orchestra’s discography.

Phillip Huscher has been the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since 1987. He studied piano at the Aspen School of Music and music history at the University of Chicago. A former journalist and music critic, Huscher has written extensively about the Chicago classical music scene for the Chicago Daily News, the Chicago Sun-Times and the Chicago Tribune. He was also the Chicago correspondent for Musical America and contributing editor at Chicago magazine for more than a decade. Huscher has written liner notes for Grammy Award–winning recordings, scripts for televised performances on PBS and program notes for many organizations, including Carnegie Hall, the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival and major U.S. orchestras. He is the author of The Santa Fe Opera: An American Pioneer, published in 2006, and currently is working on a book about the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

“The recordings I have chosen are not necessarily my favorites, in the sense that these are performances I return to again and again. They certainly do not all represent music that I love. But they reflect moments in my thirty-five years with this orchestra when something clicked in my ever-evolving understanding of the power of music — moments when the brilliance of this orchestra’s playing, the work of great conductors and the magic of the musical language itself merged to leave a fingerprint on my life that nothing can erase.”

MAHLER Symphony No. 8 in E-flat Major

Recorded in the Sofiensaal, Vienna in 1971 for London

Georg Solti conductor

Heather Harper soprano

Lucia Popp soprano

Arleen Augér soprano

Yvonne Minton mezzo-soprano

Helen Watts contralto

René Kollo tenor

John Shirley-Quirk baritone

Martti Talvela bass

Chorus of the Vienna State Opera

Norbert Balatsch chorus master

Singverein Chorus

Helmut Froschauer chorus master

Vienna Boys Choir

1972 Grammy awards for Album of the Year–Classical, Best Choral Performance–Classical (other than opera) and Best Engineered Recording—Classical

“The week I moved to Chicago, late in August 1971, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra took off on its long-awaited first tour of Europe. The first stop was Vienna, where Solti and the Orchestra were to record one of music’s most spectacular and complex scores, Mahler’s Symphony no. 8, often called the Symphony of a Thousand. I later heard Solti conduct the piece twice in Chicago, in 1977 and 1980, and I recall being struck by how Orchestra Hall seemed completely filled with sound in a way that I had never imagined possible — something no recording could possibly match. Yet that 1971 recording retained its magic as I continued to marvel at Solti’s mastery, driving straight ahead in its most congested pages and carving a clear path through Mahler’s dense web of contrapuntal lines, with eight soloists each going his or her own way, over great masses of choral and orchestral polyphony. In time, I tired of Mahler’s overheated score — today it is my least favorite of the Mahler symphonies — and now I would be quick to recommend Solti’s 1970 Chicago recording of Mahler’s Fifth, the piece that famously set Carnegie Hall ablaze when Solti led it there that year. But nonetheless, his recording of the Eighth remains for me a touchstone of the splendor and sheer sonic brilliance of this orchestra and of Solti’s volcanic energy and edge-of-your-seat intensity.”

SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No. 7 in C Major, Op. 60 (Leningrad)

Recorded in Orchestra Hall in 1988 for Deutsche Grammophon

Leonard Bernstein conductor

1990 Grammy Award for Best Orchestral Performance

“When I had worked for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for little more than a year, and was still getting accustomed to encountering giants of the music world roaming the halls, Leonard Bernstein, arguably the biggest giant of them all, came to conduct. Since I was too embarrassed to ask him for his autograph myself, we played a little charade, like something out of a Mozart opera finale — I sent an intern in my place, Bernstein insisted that I come in person, I showed up now more embarrassed than ever, we laughed, he signed a program book and we had a lovely chat. What keeps that silly memory alive, of course, is the magnificent recording he made of Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony that week. It is a marvel of razor-sharp clarity, hard-driving energy, and deeply felt, lived-in passion and angst, all conveyed with the swagger of a Broadway star. It has rarely been matched. In the last major interview he gave, a twelve-hour conversation with Rolling Stone’s Jonathan Cott in November 1989, just a year before his death, Bernstein was asked which of his four-hundred-and-some albums was most special to him. ‘I love my recording of the Shostakovich Seventh with the Chicago Symphony,’ he replied, ‘It’s more than a record can be.’”

MAHLER Symphony No. 9 in D Major

Recorded in Orchestra Hall in 1995 for Deutsche Grammophon

Pierre Boulez conductor

1998 Grammy Award for Best Orchestral Performance

“When Pierre Boulez came to conduct the Orchestra in 1987, after a long absence, I knew him by reputation only as an intimidating, formidable, fiercely critical intellectual. I was then shocked to meet a man who was so warm, kind, charming, unpretentious and wickedly funny. When we had lunch the last time I saw him, in 2010, midway through his fish entrée he offhandedly began to move his shoulders in perfect sync with the hip background music. That too was part of this many-faceted man who had set the music world on edge with his avant-garde scores and caustic comments. As a conductor, Boulez was as deeply musical — and deeply human — in his understanding of the classics as any of the podium’s historic superstars. He was also a master of fine arts restoration in the way he took familiar pieces of music and scrubbed them of the bad habits they had accumulated over the years to reveal their innate beauty, to let us see them fresh — as if they were, in fact, new scores. That is why I have always been fond of this recording of Mahler’s final symphony, his Ninth, which is often milked for every last drop of sentiment and despairing farewell. In Boulez’s hands, it is a beautiful, sobering reflection on the leaving of life. Each musical detail shines. The climaxes have rarely sounded so bracing and raw. There is simplicity, spareness and eloquence where there is often angst. Mahler’s score here appears like a huge modernist canvas, alive in its silences and its emptiness, dazzling in its sudden splashes of Rothko red. This is a performance you could live with forever; it always reveals new details, it never overacts or grandstands. It seems, somehow, just right. When I learned that Boulez had died, in January 2016, I remember thinking of the final pages of this symphony, where, in just a few scattered phrases, all the life suddenly seems to drain from music of immense primal force and humanity.”

PUCCINI Intermezzo from Manon Lescaut (from Riccardo Muti Conducts Italian Masterworks)

Recorded in Orchestra Hall in 2017 for CSO Resound

Riccardo Muti conductor

“The Intermezzo from Puccini’s Manon Lescaut is only six minutes long, but it tells you everything about Riccardo Muti’s gifts. This is music that in other hands can quickly sour, turning overly theatrical or sentimental, sounding trite, even vulgar. Only the greatest of musicians know how to reveal the music’s deepest emotions without crossing over into melodrama. Listen to what Muti does with Puccini’s melody — the way it slows and almost comes to a complete stop without ever losing the sense of line, and then winds back up again; the way it pulls and tugs at our sense of time as it unfolds naturally, seemingly spontaneously, yet with the most astonishing subtlety in its rhythmic freedom. The rush to the climax is urgent, breathless, yet perfectly paced, never rushed. There are notes that seem to linger forever — yet not a moment too long. It is this same unerring feel for pacing — knowing when to move and when to let the music breathe without losing sight of the destination — that underlies Muti’s most powerful performances, whether in these lyrical six minutes or in the complex massed ensembles of Verdi’s Otello, which in his hands become breathtaking Hitchcock-like essays in power, drama and tension.”

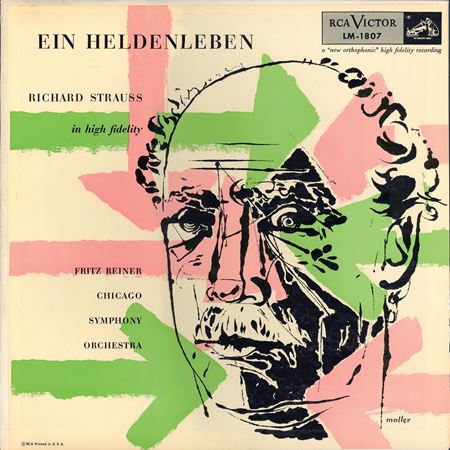

STRAUSS Ein Heldenleben, Op. 40

Recorded in Orchestra Hall in 1954 for RCA

Fritz Reiner conductor

“And one recording from the more distant past that more or less set the standard for everything that followed: Richard Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben. Recorded on March 6, 1954 — the first day RCA captured the brilliance of the Fritz Reiner–Chicago Symphony Orchestra partnership, using just three hanging microphones — this legendary recording of Strauss’s virtuosic tone poem is the definitive account of a score this orchestra practically owns: after giving the U.S. premiere in 1900, the Orchestra once played it regularly, sometimes nearly every season. It was the first work Reiner rehearsed as music director, and it quickly became a specialty of his Chicago years. Reiner was conducting Ein Heldenleben the first time Daniel Barenboim heard the Chicago Symphony, in 1958, and the fifteen-year-old was amazed by the orchestra he would one day lead: ‘It was like a perfect machine with a beating human heart.’

“From the very opening, with its volley of grand orchestral sound, Reiner is in complete command of his forces — in music of great bravado, with the famed brass section in full voice, and in the most intricate moments of chamber-music-like textures. The noisy battle scene is still one of the most chaotic passages in all music, but in Reiner’s hands you hear every line, every gesture to hair-raising effect (capped by Adolph ‘Bud’ Herseth’s fearless trumpet playing). The translucence Reiner achieves only raises the tension to an almost unbearable peak. Near the end, when the music dissolves into a grand, eloquent slow melody, Reiner captures its serenity and lyrical splendor like to no other conductor I’ve heard.

“Measure by measure, Reiner’s 1954 recording of Strauss’s Don Juan may be more electrifying: Reiner was dissatisfied with the playback and turned to the musicians and said they would have to do it again, all sixteen minutes of it, in one take, from the top, without a single mistake — which, remarkably, they did. But because of its historical significance, and the players’ astounding virtuosity in such a wide range of music, Reiner’s Ein Heldenleben will long stand as a time-capsule moment in our orchestra’s history. Four years after this recording was made, when Reiner and the Orchestra performed Heldenleben on tour in Boston, even Reiner was stunned by the magnificence of the playing; for the only time in his life, he said, he had led a ‘perfect concert.’”

A few honorable mentions:

- BARTÓK Bluebeard’s Castle with Pierre Boulez, Jessye Norman and László Polgár for Deutsche Grammophon (1993)

- BRUCKNER Symphony No. 4 in E-flat Major with Daniel Barenboim for Deutsche Grammophon (1972)

- BRUCKNER Symphony No. 9 in D Minor with Riccardo Muti for CSO Resound (2016)

- DVOŘÁK Cello Concerto with Daniel Barenboim and Jacqueline du Pré for Angel (1970)

- MAHLER Symphony No. 5 with Sir Georg Solti for London/Decca (1970)

- STRAUSS An Alpine Symphony with Daniel Barenboim for Erato (1992)

- STRAUSS Don Juan with Fritz Reiner for RCA (1954)

- VERDI Otello with Riccardo Muti for CSO Resound (2011)

- VERDI Messa da Requiem with Riccardo Muti for CSO Resound (2009)

- WAGNER Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg with Sir Georg Solti for London (1995)

MFC-045