Theodore Thomas in the early 1870s

Jeremiah Gurney & Son

More than twenty years before founding the Chicago Orchestra in 1891, Theodore Thomas and his eponymous ensemble — the Theodore Thomas Orchestra — were enjoying a wave of success. Thomas founded the orchestra in 1864 and after performing to great acclaim primarily in New York, he soon decided that traveling the country was next step in their continued success. The first tour began in the fall of 1869 and included a November residency in Chicago for three concerts in Farwell Hall.

“The first concert by Theodore Thomas’s unrivalled orchestra on Saturday evening was, without exception, the finest musical event Chicago has ever known,” reported the Chicago Tribune on November 29. “The light and shade of this orchestra are something marvelous [and] it plays with delicious expression . . . magical.”

Thomas and his orchestra returned to Chicago twice in the next year and a half, in November 1870 and April 1871. The anticipation for their returns grew and reception continued to be enthusiastic. “I think we cannot, any of us, be too grateful for such music as this,” wrote Peregrine Pickle (perhaps a nom de plume) in a letter to the editor of the Tribune on April 22, 1871. “It makes better men and women of us all [and] lifts us to a higher plane of enjoyment.”

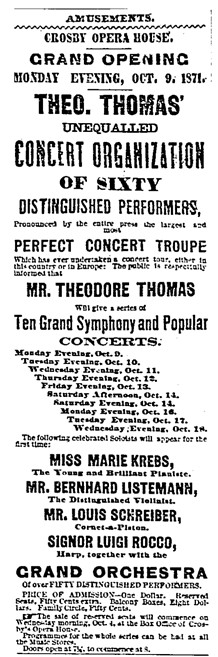

The Theodore Thomas Orchestra’s fantastic receptions during those first three residencies encouraged Uranus H. Crosby to invite Thomas to be the centerpiece for the grand re-opening of his opera house in October 1871.

Originally inaugurated on April 20, 1865 (delayed by three days due to the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln), Crosby’s Opera House was located on the north side of Washington Street between State and Dearborn. The Italianate five-story palace featured allegorical statues overlooking patrons as they passed through a grand entry arch, and residents included music publishers, William Wallace Kimball‘s piano store, business offices and art studios and galleries. The 3,000-seat auditorium featured a dome encircled by likenesses of composers surrounded by frescoes painted by the firm of Jevne & Almini, and above the orchestra was a forty-foot painting based on Guido Reni’s Aurora. The reported cost to build was well over $600,000.

Originally inaugurated on April 20, 1865 (delayed by three days due to the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln), Crosby’s Opera House was located on the north side of Washington Street between State and Dearborn. The Italianate five-story palace featured allegorical statues overlooking patrons as they passed through a grand entry arch, and residents included music publishers, William Wallace Kimball‘s piano store, business offices and art studios and galleries. The 3,000-seat auditorium featured a dome encircled by likenesses of composers surrounded by frescoes painted by the firm of Jevne & Almini, and above the orchestra was a forty-foot painting based on Guido Reni’s Aurora. The reported cost to build was well over $600,000.

Soon after the house’s initial success, Crosby ran into severe financial difficulties, and the theater sat mostly dark until undergoing a major renovation during the summer of 1871. On September 14, the Chicago Tribune announced: “The opening of Crosby’s Opera House, after the splendid refitment which it has been undergoing for several weeks, will be fitly celebrated by a season of Theodore Thomas’s symphony and popular concerts, ten of which will be given, beginning Monday evening, October 9, and ending on Wednesday evening, the 18th.”

On October 8, the “brilliantly decorated and renovated” theater was “lit up for the first time . . . for the pleasure of friends of the managers,” according to George P. Upton. A few short hours later, tragedy struck and the city was in flames, as the Great Chicago Fire rapidly spread from the southwest side to the center of downtown. Early in the morning on October 9, Thomas and the members of his orchestra “reached the Twenty-second Street station of the Lake Shore Railroad while the fire was at its height and left the burning city at once . . .”

According to Memoirs of Theodore Thomas, completed in 1911 by his widow Rose Fay: “Thomas was paralyzed by the announcement that Chicago was burning, and the Opera House already in ashes! In short, they had arrived just in time to witness the terrible conflagration which so nearly wiped Chicago off the map altogether, and, of course, the concerts which Thomas had expected to give there for two years to come, were canceled. . . . he and the orchestra stayed [in Joliet] until it was time for the next engagement in Saint Louis.”

Over 2,000 acres of land were destroyed, including nearly 18,000 buildings and well over $200 million in property. More than 100,000 Chicagoans — roughly one-third of the city’s population — were rendered homeless, and approximately 300 lost their lives.

“We got away from the burning city as best we could, and spent the time intervening before our next engagement . . . in rehearsals,” wrote Thomas in his autobiography. “We began by studying the finale of [Wagner’s] Tristan and Isolde, and I played it in connection with the Vorspiel (which I had brought out in 1865), for the first time in America [in] Boston, the following December.”

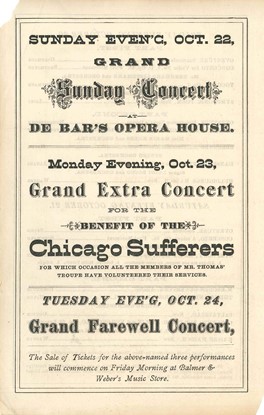

In Saint Louis, Thomas was invited to add concerts at Benedict DeBar’s Opera House, including a “grand extra concert” on Monday, October 23, “for the benefit of the Chicago sufferers, for which occasion all the members of Mr. Thomas’ troupe have volunteered their services.”

Despite initial financial setbacks due to the lost concerts in Chicago, the Theodore Thomas Orchestra would continue to mostly thrive until it was disbanded in 1888. Of course, this led the way for Thomas to establish the Chicago Orchestra in 1891 and serve as music director for the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, proving to the world that Chicago had indeed risen from the ashes.

This article also appears here, and portions previously appeared here.