Joyce DiDonato

Chris Gonz

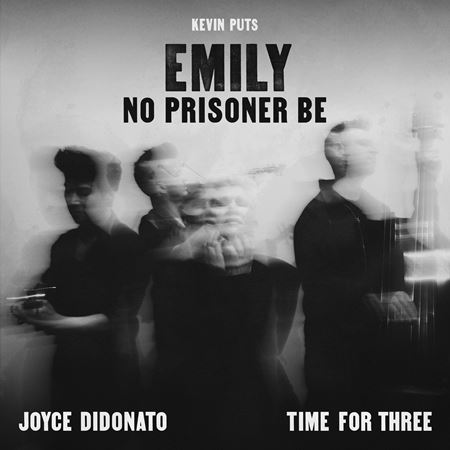

Grammy Award–winning mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato is an electric presence onstage and an extraordinary advocate for the arts. As this year’s CSO artist-in-residence — and following her September 2025 performance at Symphony Ball — in 2026 she will perform Kevin Puts’ song cycle Emily – No Prisoner Be; appear with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in Peter Lieberson’s Neruda Songs; and participate in Notes for Peace, one of the Negaunee Music Institute’s community engagement programs.

Recently, DiDonato sat down with Frank Villella, the CSOA’s director of the Rosenthal Archives, for a wide-ranging conversation.

FV: You are the third musician — and the first vocalist — to serve as CSO artist-in-residence. What are the strengths you bring to the position, how have you embraced this responsibility and what do you hope to achieve this season?

JDD: There is real potential for deeper impact with a residency. I have found in previous encounters that the sense of community deepens when I return for several appearances in a curated season. It offers the chance for me and the audience to know each other more, which can deepen the experience in the concert hall. My hope is to confirm for the audience and supporters how valuable and, in truth, necessary these communal experiences in music are.

Poetry and storytelling play a huge role in the music you perform. Do you have any favorite poets? Have you ever tried your hand at writing poetry?

Right now it’s all Emily, all the time. I performed Aaron Copland’s Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson on my senior recital at Wichita State University and then chose them for my first solo recital album. So she has always been a part of my artistic journey. And while I love to write and do so often for myself, it might horrify Emily, because it’s nearly always prose. But you have just raised the challenge for me — perhaps that’s a resolution for 2026!

Can you describe the genesis of the Emily – No Prisoner Be project, in collaboration with composer Kevin Puts and the classical-roots trio Time For Three? How did your experience in the creation, performance and recording of Puts’ opera The Hours influence the experience of Emily and your decision to continue to work with the composer?

I was singing Virginia Woolf in Kevin’s opera The Hours and he approached me with the beautiful message that he wanted to write more music for me. He then asked if i knew Time for Three, and at that point I had only heard their name — I knew they had recently won a Grammy for Kevin’s concerto Contact, but that was all I knew. Kevin said, “I just think you guys will really hit it off.” (He must be a fortune teller!) The very next statement was, “and I’m thinking about Emily Dickinson — I just found this poem ‘They shut me up in Prose’ and I can already hear the music.” Before I knew it, we were in a studio workshopping his music, and our project was taking flight. Kevin has such a clear and inventive way of composing, and at the same time he is indescribably collaborative — so I didn’t even hesitate for one moment to say, “yes.”

Joyce DiDonato with Time for Three

Lorenzo Cisi

This coming May, we will also hear you in Peter Lieberson’s Neruda Songs. Did you meet or have any connection to the composer and/or the dedicatee, his wife Lorraine Hunt Lieberson? When did you first hear the cycle and what made you want to perform the songs?

I met Peter in 2009 as he had written an oratorio for me, The World in Flower, which I premiered with the New York Philharmonic. We spoke then of the Neruda Songs and that he hoped I would sing them one day. It felt a bit soon after Lorraine’s passing to sing them at that time, but this cycle has always been in my mind. I’m so glad Maestro Edward Gardner thought to program these. It will be a great honor to sing these finally.

The Neruda Songs are deeply personal, not only because of Pablo Neruda’s poetry but also their connection to the composer and the original interpreter. How do you approach a work like that — similar to, for example, your performance of “Over the Rainbow” at Symphony Ball this past September — one that is so closely connected to the person for whom it was written?

I go straight to the score. Peter was a very clear, very beautiful composer, and you can feel immediately the deep connection and love that runs through every phrase of this cycle, and it is all there on the page. As we work to bring it to life, I will stay very connected to the poetry and the colors of his score, presenting it in a way that really honors all the creators of this piece and allows the audience to make their own connection to this moving cycle.

During your first residency with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 2016, you collaborated with Riccardo Muti in the Juvenile Prison Partnerships program at the Illinois Youth Center in Warrenville. Can you describe that experience and what impact it may have had on the participants and on you?

That was such a meaningful afternoon in so many ways. It was beautiful to see Maestro Muti come to life in such a dynamic way as he interacted with the young people there. It was almost as if he became a child himself as he connected with them through the music. This work is absolutely vital. It reconnects all of us to a common humanity. Those who are detained in the facility oftentimes feel less than human, and to have people come in, connect directly with them and SEE them, LISTEN to them. It can have powerful transformative effects in their lives. And, of course, that is a two-way street. We are all humbled because to sit with people who receive the music in such a nourishing and impactful way reinforces for us working musicians just how vital and powerful sharing music is.

You have spent so much of your career performing and recording the music of Rossini, Mozart and Handel, and you are also a major proponent of works by contemporary composers. What draws you to these composers and their works? What are the pieces that you could enjoy performing over and over again?

I have a voracious musical and dramatic appetite, and luckily I was born a mezzo-soprano, so the range of genre, character and quality is immense for me. I have relished exploring so many corners of the musical worlds, and I hope it never stops. I find that one genre/character/experience always feeds the others, extending my tool box, my color choices, my musical vocabulary! What I look for in a project or a piece of music is deep emotional connection and a kind of musical imprint that will last with the listener. As long as it is true, connected and helps tell a meaningful story, I can sing anything over and over again!

Early in your career, what was the best advice you received? What’s the advice you try to pass along to the next generation of musicians?

Early advice I think was quite valid was, “If there is anything else at all that I could see myself doing in this life — do it. Because the career is too challenging if you don’t have to pursue it.” I do think that’s essentially true — but it can be daunting if you’re not yet sure early on. I do try to remind young singers (not to mention older ones!) to be sure we are not giving away the power of our own joy to anyone else. We got into this because we LOVE making music — that should be protected at all costs.

What music do you listen to in your spare time? What moves or inspires you, particularly music you might never perform? Which great singers — of any genre — do you most enjoy?

I love Arabic music (duduk!), choral music, Brazilian music . . . beautiful music! And for me, Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan are TITANS of vocal coloring and expression.

Your master classes are legendary. As you look ahead to the upcoming series at Carnegie Hall in April 2026, among others, what do you like most about working with young singers? What do you hope they take away from working with you and what do you learn from them?

I’m always interested in reminding them that no one will give them permission to be the artist they want to be. That permission must come from them. They must be fearless and do the work of removing the obstacles that constrain their artistry. Sometimes that may be technical work, sometimes it is psychological or spiritual. We singers are brilliant at standing in our own way of expressing what we really have to say from deep within. I love helping to unlock that in anyone!

____________________________________