CSO principal tubas Arnold Jacobs (left) and Gene Pokorny take centerstage in the just-published book "The Perfect Tuba."

Journalist Sam Quinones was done with drugs.

For 12 years, first as a reporter for the Los Angeles Times and then as a freelance author of two highly praised books, he had researched and written about the ways that drug addiction was ravaging the American landscape. Burned out after so many years on that chronically grim beat, he was ready for a change.

How big a change? Two years ago, Quinones shifted most of his focus to one of America’s most beloved and enduring symbols of high spirits and good cheer — the marching band. And in particular, its most smile-inducing instrument — the tuba.

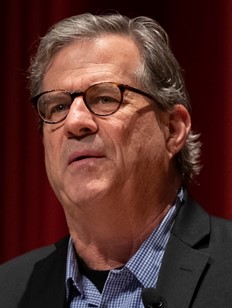

The result is his newest book, The Perfect Tuba (Bloomsbury Publishing), a lively, fast-paced immersion in the world of marching bands and tubas. Quinones (at left) is a gifted storyteller, and his cast of memorable characters is vast and vividly drawn. There’s the Florida seventh grader, anxious to get out of home ec., who joined the school band on the condition that he play the tuba. Sure, he replied. What’s a tuba?

The result is his newest book, The Perfect Tuba (Bloomsbury Publishing), a lively, fast-paced immersion in the world of marching bands and tubas. Quinones (at left) is a gifted storyteller, and his cast of memorable characters is vast and vividly drawn. There’s the Florida seventh grader, anxious to get out of home ec., who joined the school band on the condition that he play the tuba. Sure, he replied. What’s a tuba?

And there’s H.E. Nutt, the ascetic co-founder of Chicago’s VanderCook College of Music, who trained generations of band directors, starting in the late 1920s. His highly practical teaching methods still influence junior high, high school and college band teachers today.

“People came from all over to study in Chicago,” said Quinones in a recent video interview from his home in Nashville. And, as outlined in the book, VanderCook graduates scattered across the 50 states to create scores of award-winning marching bands. Some of their students, most of whom had never picked up a tuba before walking into band class, became acclaimed professional tuba players.

The Chicago Symphony also plays a major role in tuba history. The symphony’s brass section has its own kind of renown beyond the CSO’s longtime status as one of the world’s finest orchestras. Students and professionals by the hundreds came to Chicago for individual lessons with Arnold Jacobs, the CSO’s legendary principal tuba from 1944 to 1988. In addition to being one of the finest musicians ever to hoist that weighty horn, he became an expert in the physical properties — breath control, lung capacity, muscle tone — that tubists need to master their art.

And when Jacobs arrived at the CSO from the Pittsburgh Orchestra, he came with a tuba he had purchased as a student for $175 on a $5-a-week installment plan. In the early 1950s, he bought another, also made in the 1930s by the same manufacturer, York Band Instrument Co. in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Now owned by the CSO, they turned out to be the finest tubas ever made and virtually impossible to duplicate. Known as the Chicago Yorks, the instruments, as Quinones tells it, are considered the “Holy Grail of tubas.”

Gene Pokorny, CSO’s current principal tuba, who succeeded Jacobs in 1989, arrived in Chicago with a copy of a Chicago York made by Hirsbrunner, a respected Swiss manufacturer. He was surprised that the CSO had bought Jacobs’ instruments.

“I thought that was kind of strange because [tuba manufacturers] were making copies all over the place,” Pokorny said in a video interview. “They keep getting close; they’re all very good instruments. But it wasn’t until I got into the orchestra and actually picked up those instruments that I realized that Hirsbrunner may have made a copy, but it certainly didn’t sound anything like the original York tuba.”

One problem, according to Quinones, is figuring out exactly what kind of brass the York technicians used.

“It’s 80 percent copper and 20 percenr zinc,” he said. “But where did that brass come from, because it was never commercially made in the U.S. That’s one of the wonderful mysteries about these York tubas. There’s a myth that Pops Johnson, the foreman, supervisor and toward the end, the owner of the York company, threw dirt into the mix of brass he would get. I don’t have any clue if that’s true.”

York shifted to manufacturing items for the military during World War II, Quinones writes. The artisans who had figured out how to make the world’s finest tubas eventually drifted away, taking their institutional knowledge with them.

Quinones quotes one tubist’s description of the York sound: “Broad, possessing great power and volume on the one hand, yet having a beautiful singing core on the other.”

To Quinones’ ear, the sound isn’t so much heard as felt. “Not only is it big and rich. It also blends with the other instruments while standing out too, but in a good way.”

Professional tuba players periodically come to Symphony Center for what Pokorny describes as “cattle calls.” They bring their instruments and play for one another. They play them onstage and go out into the hall to hear how their own tubas sound from the audience.

At the end of the evening, Pokorny usually brings out the Chicago York he most often plays.

“There’s this ‘a-ha!’ moment. Or maybe it’s more like ‘ooh,’ ” he said, giving a dispirited groan. “I have a feeling every tuba manufacturer would like the original Yorks to just disappear. It places everything in a wider perspective that’s really difficult.” The tubists especially praise the York’s “sweet, organic” sound, he said.

“I realized that in Mexican Los Angeles, the tuba was an extraordinarily popular instrument. It was what the guitar had been when I was growing up in Southern California. It was really, really a big deal.” — Sam Quinones

“Sweet” and “organic” may not have been what Quinones expected to find when he started exploring the tuba world. He arrived at the Los Angeles Times in 2004, after a decade living in Mexico.

“I was reporting about issues related to Mexican L.A.,” he said. “Along the way I realized that in Mexican Los Angeles, the tuba was an extraordinarily popular instrument. It was what the guitar had been when I was growing up in Southern California. It was really, really a big deal. Trumpet players were switching to tubas because they got paid triple.”

Black-market dealers would steal tubas from high schools and sell them to wanna-be tuba players. The tuba was probably popular due to its importance in banda music, a Mexican style grounded in brass, especially tubas and trumpets, and clarinets.

Knowing a good story when he heard one, he wrote about the phenomenon. And his interest in tubas never waned.

“Strangely, and I can’t really explain why, I just kept interviewing tuba players. I kind of stopped with the Mexican tuba world and expanded out into Disney and the classical world. It was a subject I knew nothing about. I don’t play the tuba. I was never in a marching band.”

But Quinones is a reporter fascinated by worlds he knows nothing about. And tuba players were a refreshing change from the frequently dead-end lives of the drug addicts he had written about.

“The folks in [the tuba] world were doing something for the love of it,” he said. “Nobody gets rich and famous playing the tuba. And almost always, when somebody’s doing something for the love of it, there’s a great story there.

“It was really an attempt to break away from writing about addiction — people who sought happiness through something they purchased,” he said. “I wanted to write about people who found fulfillment in honing and cultivating their own talents from within.”

The book’s subtitle is “Forging Fulfillment From the Bass Horn, Band and Hard Work” — with emphasis on the “Hard Work.”

Purchase ’The Perfect Tuba’ at the Symphony Store

“Most people who play the tuba don’t want to play the tuba initially,” he said. “They just happen to be late for band class one day, and all the other instruments are taken. I heard that story many times. What happens then, however, is fascinating. These same people worked hard at the tuba. They grew to find themselves in the tuba, and the tuba showed them what they were capable of.”

In a way, gaining mastery of the tuba — or whatever other difficult thing you work hard to achieve simply for the love of it — is its own kind of drug, Quinones said.

“That is a narcotic. All of a sudden, ‘I am more than people think I am. I can do more than people think I can do.’ Tuba endowed a lot of people with that feeling. It’s very intoxicating.

“I’m writing for 12 years about people who are looking for their happiness from some piece of crud they buy from the motel down the road. Here you’re looking at people who are entirely motivated by something entirely different: ‘I want to find what makes me feel like I’m worthy, that I can do things. It shows me my own capabilities.’ That’s a radical, and beautiful, idea.”