Jacqueline du Pré in 1967

Godfrey MacDomnic

On January 26, 2025, we celebrate the 80th birthday of the remarkable English cellist Jacqueline du Pré (1945–1987), who performed and recorded with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1969 and 1970.

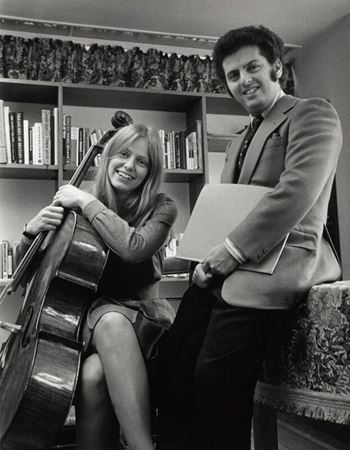

According to her husband — and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s ninth music director from 1991 until 2006 — Daniel Barenboim in his autobiography A Life in Music: “Jacqueline’s way of playing did not really change from the time she was a teenager . . . Even then, she played with incredible intensity and vivacity. Obviously she continued to develop, but the basic personality and character of her cello playing was established at a very early age. Of all the great musicians I have met in my life, I have never encountered anyone for whom music was such a natural form of expression as it was for Jacqueline. With most musicians you feel that they are human beings who happen to play music. With her, you had the feeling that here was a musician who also happened to be a human being. Of course, one had to eat and drink and sleep and have friends. But with her the proportions were different — music was the center of her existence.”

Du Pré only appeared with the Orchestra a handful of occasions. But those occasions were notable not only for her playing but also because of the conductors with whom she shared the stage.

In February 1969, Pierre Boulez made his debut guest conducting appearances with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The first week included Barenboim’s subscription concert debut as piano soloist, and on the second week’s program, du Pré made her debut with the Orchestra, as soloist in Schumann’s Cello Concerto in A minor.

In the Chicago Sun-Times, Robert Marsh called her performance, “gloriously impetuous,” while Thomas Willis in the Chicago Tribune raved, “The immensely gifted young cellist . . . plays for keeps all the time. Each note has maximum persuasive power. There is a total commitment of both physiological and musical resources. The melodic line is maximally weighted. When she is not playing, she is often reacting to the orchestral dialog — so much a part of the Schumann concerto.”

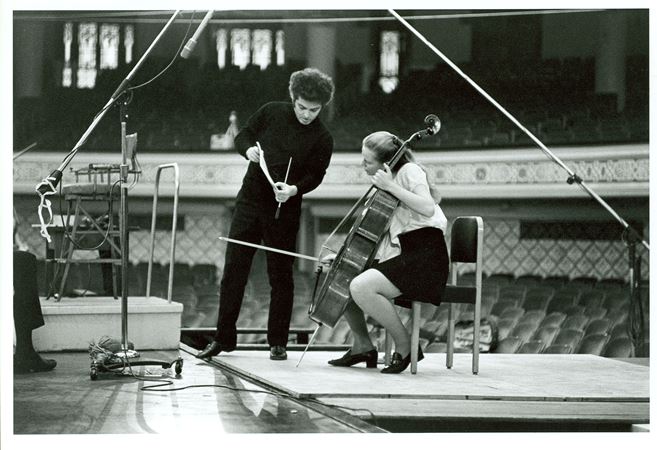

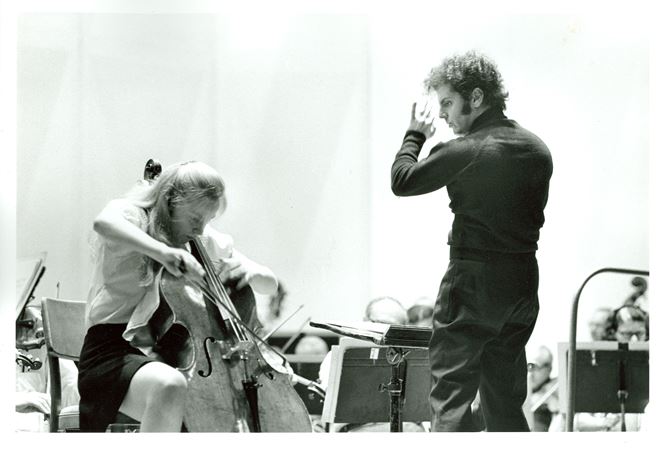

Later that year in November, Georg Solti made his first appearances as music director. The centerpiece of his first program was Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor with du Pré as soloist.

“Georg Solti began his tenure as the eighth music director in a festive and highly auspicious manner,” continued Willis. Du Pré “fashions her own concept. She is absolutely in command of her Stradivarius and delights in showing it. Not just in the virtuoso command of the double stops, bouncing bow, and high position fingerings which make this work the standard proving ground for cellists, tho. The long notes get special caresses, a flick of vibrato just as they threaten to turn lifeless, or a push above true pitch for emphasis. Few performers at any age can keep listeners as engrossed . . .” Marsh added, “She played it with such total conviction . . . Miss du Pré is real musical personality with real temperament and real insight and all these things project so forcefully to her audience . . . She demands that you respond to her. And you do.”

In November 1970, du Pré and Barenboim returned to appear in a series of concerts at Michigan State University as part of a festival celebrating the bicentennial of Ludwig van Beethoven. The pair presented an evening of chamber music on November 2, and Barenboim gave an all-Beethoven piano recital the following night. On November 4, Barenboim made his conducting debut with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the first piece on the program was Dvořák’s Cello Concerto. Two days later, du Pré was soloist in Saint-Saëns’s Cello Concerto, also with Barenboim on the podium.

In the Lansing State Journal after the November 4 concert, Winnifred Sherburn commented: “Miss du Pré, cello soloist with the symphony, must be heard and seen to be believed. Her beautiful playing of the Dvořák Concerto for Violoncello enthralled the capacity audience. Barenboim, who conducted, gave the most sensitive support, perfectly controlling the ensemble. The effect was that of a large orchestra listening to a solo instrument with the closest attention. . . . Though loosely knit, the music was brilliant and dramatic and Miss du Pré played it gloriously with all her wonderful tone, technique, and style.”

Later that week in the Journal, Mary Perpich wrote: “But it was Miss du Pré that took the audience’s hearts with her unique rendering of the Saint-Saëns concerto. She is fascinating to watch. Looking almost childlike in her full-length evening gown of purple and green with her long, blonde hair pulled back from her face, the 25-year-old master musician perched on a chair next to her husband and began her thoroughly captivating performance. And while she played she seemed to go into a trance, caressing the cello lovingly as if it were a newborn child, head moving gently from side to side, she and her instrument produced beautifully tempered music. She broke the spell only twice to watch her husband cue and smile triumphantly at the orchestra concertmaster. The audience brought her back for five bows before she finally left [the] stage.”

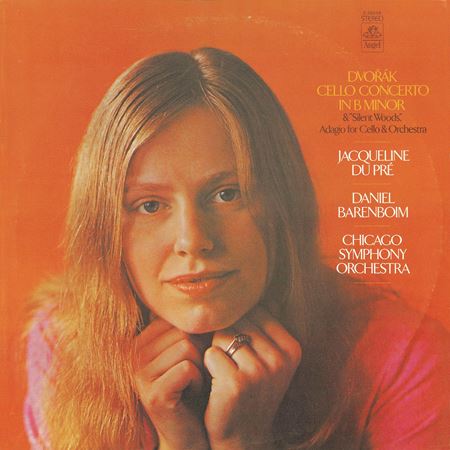

On November 11, 1970, at Medinah Temple, du Pré committed Dvořák’s Cello Concerto and Silent Woods to disc with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Barenboim, in his first recording with the ensemble, was on the podium. For Angel Records, Peter Andry was the producer and Carson Taylor was the balance engineer. It was released the following year and has never been out of print.

This article also appears here.