Germany’s Rhine Valley, the fairytale-like world of forested hillsides, medieval castles and the expansive Rhine River, is the backdrop of Civic’s first concert of the season.

This at-a-glance portrait of the works included on this program is adapted from program notes by CSO Scholar-in-Residence and Program Annotator Phillip Huscher and composer Gabriela Ortiz.

WAGNER Siegfried’s Rhine Journey from Götterdämmerung

Siegfried’s Death was the original title of the prose sketch for an opera that grew, over the span of twenty-eight years, into the most monumental undertaking in the history of music—Richard Wagner’s four-opera cycle The Ring of the Nibelungen. The murder of the young hero Siegfried was Wagner’s starting point, and it remains the climax of the full seventeen-hour work.

Siegfried’s Rhine Journey, one of the most celebrated excerpts from the Ring, is drawn from the end of the Prologue to Götterdämmerung and serves as an orchestral interlude into the first act. The music begins at dawn, as the lovers Brünnhilde and Siegfried awaken, and Brünnhilde sends Siegfried off into the world. We hear Siegfried’s horn calls from afar and then vigorous music that moves rapidly across great vistas. Engelbert Humperdinck, who arranged the excerpt for concert performance, was an ardent Wagnerian and the music teacher of Wagner’s son, not coincidentally named Siegfried.

ORTIZ Clara

Born into a musical family, Gabriela Ortiz has always felt she didn’t choose music — music chose her. Her parents were founding members of the group Los Folkloristas, a renowned music ensemble dedicated to performing Latin American folk music. Ortiz grew up in the cosmopolitan, thriving metropolis of Mexico City, where she had a multifaceted music education. Ortiz’s music incorporates seemingly disparate musical worlds, from traditional and popular idioms to avant-garde techniques and multimedia works, with perhaps the most salient characteristic of her oeuvre being an ingenious merging of distinct sonic worlds. While Ortiz continues to draw inspiration from Mexican subjects, she is interested in composing music that speaks to international audiences. Her music reveals a sophisticated compositional technique and meticulous attention to rhythm and timbre.

Gabriela Ortiz on Clara

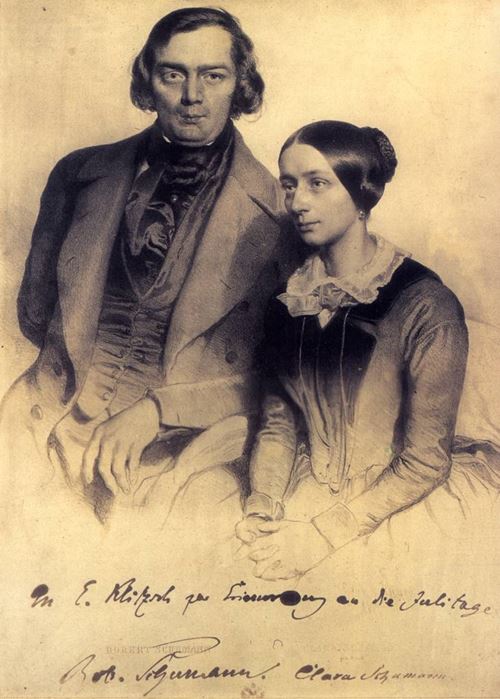

I cannot begin to discuss Clara without first thanking Gustavo Dudamel for his generosity in having invited me to compose a work based on the relationship between two great artists: Clara Wieck Schumann and Robert Schumann. Thanks to him, I was able to delve into the broad legacy of both more deftly, especially that of Clara, who, in addition to being a splendid composer and one of the most important pianists of the nineteenth century, was the editor of her husband’s complete works, as well as a teacher, mother, and wife.

Clara is divided into five parts that are played without interruption: “Clara,” “Robert,” “My Response,” “Robert’s Subconscious,” and “Always Clara.”

Except for “My Response,” all of these sections comprise intimate sketches or imaginary outlines of Clara and Robert’s relationship. My original idea was to transfer onto an ephemeral canvas the internal sounds of each one without attempting to illustrate or interpret but simply voice and create, through my ear, the expressiveness and unique strength of their complex but fascinating personalities.

. . . Throughout history, women have had to overcome major obstacles marked by gender differences. We have gradually unfolded within the musical arts with great difficulty. However, as is well known, there are many of us who have rebelled against these evident forms of injustice and struggled to gain recognition and a place in society. This piece represents an acknowledgment of Clara, a tribute to her, and my definitive, resounding response to her question. It also signals my gratitude to all the women who, in their time, challenged the society they were raised in by manifesting their artistic oeuvre.

Reprinted with permission form boosey.com

SCHUMANN Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major, Op. 97 (Rhenish)

Robert Schumann, Josef Kriehuber (1800–1876)

Robert Schumann’s medical history is full of mysterious ailments and breakdowns, depression, hallucinations, persistent trembling, a recurring fear of sharp metal objects, and—most painfully for a musician—tinnitus, a constant ringing in the ears.

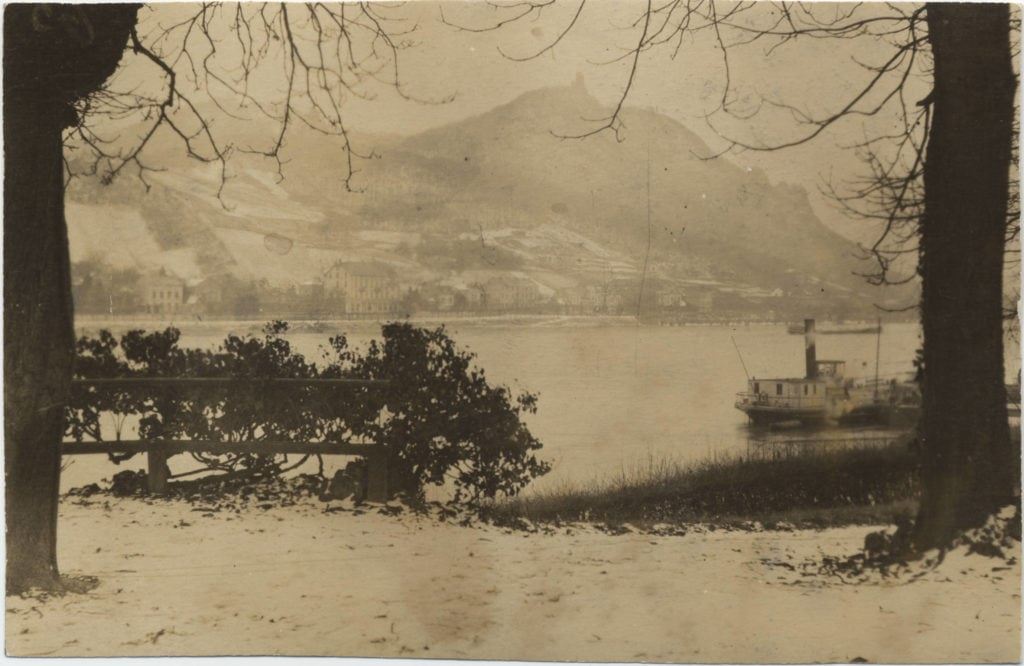

In February 1854, just before he was institutionalized, he was haunted by devils and visited by angels who sang to him in E-flat; he finally ran out of the house and threw himself into the Rhine. The fishermen who saved him and took him home to his wife, Clara, didn’t recognize one of Düsseldorf’s most distinguished citizens, the famous composer who, only four years earlier, had written his last symphony in loving tribute to the Rhine River.

Even in 1850, when Schumann began this E-flat symphony, he wasn’t in the best of shape. He and Clara had recently moved to Düsseldorf—with some misgivings once he learned of the asylum there, for he didn’t like to be reminded of mental instability. At first, Schumann was unable to compose there because of the street noise. A visit to Cologne in late September 1850 greatly inspired him; in October, he began his cello concerto and on November 2, a new symphony in E-flat. The first movement was sketched in a week, and despite taking time out for another trip to Cologne, Schumann finished the entire work by December 9.

Although Schumann is sometimes criticized for being unsympathetic to the symphonic language, the magnificent opening of this E-flat symphony argues otherwise. Here is a grand, striding theme that is broad and powerful, obviously conceived in orchestral terms and ideal for symphonic treatment—Schumann writing for orchestra with the same command we find in his piano music. Schumann originally called this music “a piece of life by the Rhine.” He had already captured the Rhine in song—the majestic “Im Rhein, im heiligen Strome” (In the Rhine, in the holy river) from Dichterliebe—but now, working with the full orchestral palette, Schumann creates one of the great German romantic musical landscapes. It’s a landscape by suggestion, for this isn’t a programmatic symphony; like Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, it is “the expression of feelings rather than painting.”