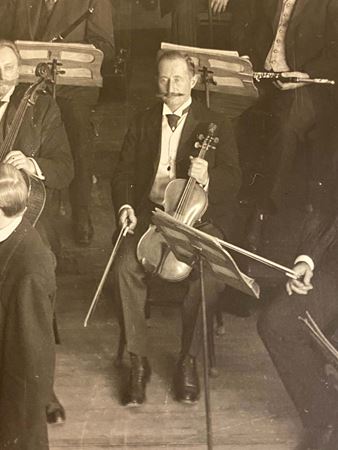

Riccardo Muti leading the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in Orchestra Hall

Todd Rosenberg Photography

Six degrees of separation is the theory that all people are no more than six social connections away from each other. It is usually used to connect living individuals, but we also can stretch it back to link people through history.

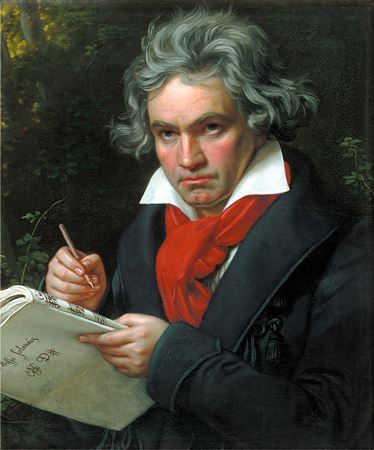

Throughout his career, Riccardo Muti has been connected to the music of Ludwig van Beethoven. During his tenure as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s tenth music director, he has conducted all of the composer’s major orchestral works — including the nine symphonies — and he will conclude his tenure with the monumental Missa solemnis. So, how might Maestro Muti be connected to Beethoven? Let’s find out, perhaps through the historic roster of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra . . .

Beginning with his debut in 1973 and continuing through his tenure as music director, Muti has collaborated with two musicians who hold the record as the longest-serving members of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra: Lynne Turner, second harp, and Jay Friedman, principal trombone. Both were hired by sixth music director Fritz Reiner in October 1962, and in June 2023 both will complete their 61st seasons as members of the Orchestra. (The record previously was held by Adolph “Bud” Herseth, who served for 56 seasons, 54 as principal trumpet.) Turner, who first performed with the CSO as a soloist on youth concerts at the age of 14, joined the Orchestra shortly after becoming the first American to win top prize in the International Harp Contest in Israel. Friedman, after four years as a member of the Civic Orchestra of Chicago and two with the Florida Symphony, was hired as assistant principal trombone, and in 1965, he was promoted to principal by seventh music director Jean Martinon.

Turner and Friedman performed for several years alongside colleagues Milton Preves and Frank Crisafulli, each of whom served in the Orchestra for over 50 years and were both hired by second music director Frederick Stock. Preves joined the Orchestra’s viola section in 1934, became assistant principal in 1936 and principal in 1939, remaining in that post for 47 years until his retirement in 1986. Crisafulli began his tenure in the trombone section in 1938, serving as principal from 1939 until 1945 and again from 1946 until 1955. He retired in 1989.

Preves and Crisafulli certainly would have known Franz Esser and Hjalmar Rabe, also members of the Orchestra for more than 50 years. Esser joined the violin section at the beginning of the second season in 1892, later serving as principal viola from 1898 until 1926 and principal second violin from 1926 until 1939; he retired in 1945. Rabe joined the violin section in 1895 but also played the bassoon; he was principal of that section for one season, 1918–19, and also principal contrabassoon in his final season, 1944–45.

Of course, both Rabe and Esser were hired by the Chicago Orchestra’s founder and first music director Theodore Thomas.

That brings us up to four degrees: Muti to Turner and Friedman to Preves and Crisafulli to Esser and Rabe to Thomas.

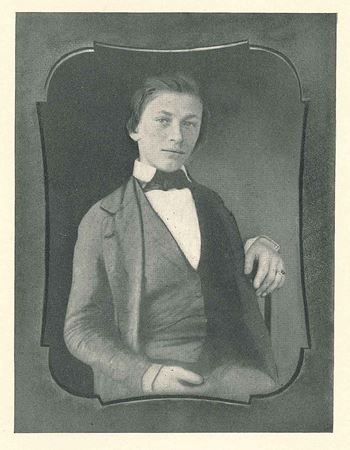

In early 1850, 14-year-old Theodore Thomas was performing in New York as a violinist in pit orchestras. He caught the attention of Karl Eckert, who hired him into the Italian Opera Company as leader of the second violins. Eckert was succeeded the following year by composer, violinist, and conductor Luigi Arditi, who promoted Thomas to the role of concertmaster as well as contractor to engage the members of the orchestra. As a member of the Italian company, Thomas had a front-row seat to hear and collaborate with two of the most important musicians of the day: Swedish soprano Jenny Lind (also known as the “Swedish Nightingale” whose American tours were organized and promoted by none other than P.T. Barnum) and German soprano Henriette Sontag.

In 1823, Carl Maria von Weber heard Sontag — then only 17 — in Vienna, in Rossini’s La donna del lago and offered her the title role in his new opera, Euryanthe, which premiered to great success later that year. Her career continued to flourish as she performed throughout Europe. Her single tour to the United States was in 1852 and included several performances with the Italian Opera Company in New York, with then 16-year-old Thomas in the pit.

Thomas expressed in his autobiography: “I do not remember another singer in whom art and experience were combined with such freshness and quality of voice. . . . neither of these exceptional women conquered the world with voice and execution alone. It was the perfection and blending of these qualities, together with the single aim—that of truthful expression, which gave greatness to whatever they rendered. I have never heard their equals.” And according to Thomas’s widow Rose Fay in the Memoirs, “nothing was more helpful to young Thomas [and] at this time the greatest singers the world has ever heard were singing in New York. . . . [Lind and Sontag] possessed the true secret of tone quality, and it occurred to him that the same kind of tone which they produced with the voice could also be created on the violin . . . as he listened to these great artists . . . he endeavored to reproduce their singing, tone for tone, on his beloved instrument.”

Nearly 30 years before her United States tour, 18-year-old Henriette Sontag sealed her place in music history. On May 7, 1824, in Vienna, she was the soprano soloist in three sections — Kyrie, Credo, and Agnus Dei — of the Missa solemnis and the premiere of the Ninth Symphony, conducted by the composer, Ludwig van Beethoven.

That’s six degrees of separation, mostly through the Chicago Symphony Orchestra family: Riccardo Muti to Lynne Turner and Jay Friedman to Milton Preves and Frank Crisafulli to Franz Esser and Hjalmar Rabe to Theodore Thomas to Henriette Sontag to Ludwig van Beethoven.

This article also appears here.